Smoking in Australia

General facts

- Smoking is the largest single preventable cause of death and disease in Australia. 1

- Smoking kills almost 21,000 Australians every year. 2

- It is estimated that seven in ten deaths from drug-related causes (tobacco, alcohol, and drug use) are due to tobacco smoking. 2

- Two in three lifetime smokers will die from their addiction. 3-5

- Smoking costs the community $137 billion per year. 6

- In 2019, the smoking rate among Australians (aged 14 years and over) was 12%. The smoking rate has halved since 1995. 7

- Most adults who smoke first tried cigarettes when they were teenagers. 7, 8

- In 2018, more than half of all Victorians who smoke had tried to quit in the past year. 9

- Nicotine found in tobacco and most e-cigarette products is highly addictive. 10, 11

- Use of e-cigarettes has increased in recent years in Australia, particularly among people aged 15 to 24 years old. 7

- Using e-cigarettes that contain nicotine can result in nicotine addiction and increases the likelihood of smoking cigarettes among non-smokers. 12

- Chemicals in e-cigarettes are not tested and can be harmful. The long-term health effects of e-cigarettes are not known. 11, 12

How many school students smoke?

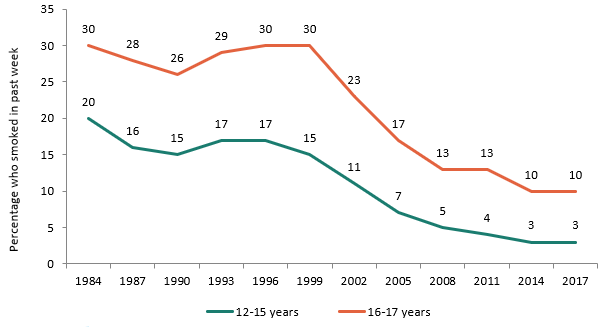

Prevalence of smoking among 12 - 17 year olds* in Australia: 1984 – 2017

In 2017, the overall rate of current smoking among Australian students aged 12 to 17 years was 5%. 13

- Among 12 to 15 year olds, 3% were current smokers; the smoking rates for males and females were both 3%.

- Among 16 to 17 year olds, 9% were current smokers; the smoking rate for males was 10% and for females 9%.

Since 1999, smoking rates among students have dropped by around two-thirds, as shown in the graph below.

*Current Smoker: Students who had smoked tobacco on at least one day in the week prior to the survey

High levels of tobacco control activities in the community have contributed to the drop in smoking rates among students. These include public education mass media campaigns, increases in tobacco tax, restrictions on the advertising and sale of tobacco products, smoking bans in public places, plain packaging of tobacco products, graphic health warnings on packs, and an increase in smokefree households with children. 8, 14, 15 Education and tobacco control measures are important so that young people understand the harms of smoking and secondhand smoke, and are therefore less likely to start smoking.

Who is most at risk of taking up smoking?

Young people are more likely to smoke if their parents, siblings or friends smoke. Students who smoke are more likely to feel more negatively towards school, to miss school more often, to perform less well academically, to engage in early school misbehaviour, and to drop out of school at an earlier age than non-smokers. 8

Australian research has shown consistently that young people living in households where English is spoken are more likely to smoke than those living in households where a language other than English is the first language. 8 Smoking rates are also higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. 8

While most forms of tobacco advertising have been banned, children are being increasingly exposed to tobacco advertising and branding through the internet and social media, including Facebook and YouTube. In an Australian survey, younger children, girls, children from poorer backgrounds and children who have never smoked were more likely to report seeing tobacco promotions online. 16

Weight control is often cited as a reason for starting to smoke, particularly among teenage girls. 17 Taking up smoking does not usually lead to weight loss. Smoking can lessen weight gain, but very slowly over many years and any effect of smoking on the average weight among young people is very small. 18, 19

What are the health effects of smoking on the young?

Smoking harms nearly every organ in the body. It causes lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, lung diseases such as emphysema, several other cancers, male erection problems, plus diseases affecting the eyes, gums, blood vessels, bones and gut. 20, 21 The younger someone starts to smoke, the more likely they are to be heavy users of tobacco, and consequently, the greater risk they have of ill health from smoking. 22

Young smokers report having poorer general health than their non-smoking peers. 18 Smoking during adolescence or childhood causes respiratory and asthma-related symptoms including shortness of breath, coughing, phlegm and wheezing. Smoking impairs lung growth and causes the early onset of lung function decline during late adolescence and early adulthood. 20 Young people who smoke have an increased risk of developing early signs of heart disease. Smoking also affects dental health and bone mass. 18

Teenagers who smoke also report higher stress levels than non-smokers, in part due to re-occurring nicotine withdrawal symptoms. 23

Immediate effects of smoking include a rise in heart rate and blood pressure, shaky hands, and a drop in skin temperature as blood vessels constrict in fingertips and toes. 10, 24 = Nicotine makes the heart work harder. 10 Carbon monoxide reduces the ability of blood to carry oxygen and the ability of muscle cells to take up oxygen. 20 Peak exercise performance is reduced. 10, 18

Keeping fit is also a lot harder if you smoke. Those who smoke: 18, 25

- are more easily exhausted

- suffer shortness of breath

- have reduced endurance

- have a blunted heart rate response to exercise.

How fast does nicotine addiction occur?

Nicotine is the addictive drug in tobacco smoke. Evidence shows that nicotine addiction can be developed rapidly by young people, with adolescent smokers reporting some symptoms of dependence even before they start smoking on a daily basis. On average, these symptoms appear within two months of starting to smoke, and mark the start of loss of control over their smoking. 22, 26 = Research shows that young people may make many unsuccessful attempts to quit even before they start smoking daily. 26

E-cigarettes: a new route to nicotine addiction

E-cigarettes are not harmless. Using e-cigarettes that contain nicotine can result in nicotine addiction and increases the likelihood of smoking cigarettes among non-smokers. 12 There is growing evidence that e-cigarette use can be harmful to health. In young people, they may increase coughing and wheezing, and trigger asthma attacks. 12

An e-cigarette is a battery-powered device that heats a liquid (called ‘e-liquid’) to produce a chemical vapour, which the user inhales into their lungs. This is known as vaping or Juuling (so-called after a popular brand among teenagers). The ingredients in e-liquids vary, but they typically contain a range of chemicals including solvents and flavouring agents, and may or may not contain nicotine. 27 E-cigarettes come in many shapes and colours and may look like cigarettes, or everyday items such as pens or USB devices. 28

Under Australian poison laws, it is generally illegal to sell, possess or use e-liquid containing nicotine. E-cigarettes and e-liquids that do not contain nicotine can be sold in stores, although under state laws the sale of e-cigarettes to people under the age of 18 is not allowed. 29 Testing of e-liquid samples by various agencies has shown they are often not labelled properly: more than half of e-liquid samples labelled as non-nicotine actually contained nicotine. 27, 28, 30, 31

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) regulates products containing nicotine that the makers claim help people stop smoking (like the nicotine patch for example). The TGA’s regulatory process requires companies to supply evidence on what’s in it, how well it works and how safe it is. To date, e-cigarette companies have not satisfied these requirements and the TGA has not approved any nicotine e-cigarette for sale in Australia. 29

Among Australian high school students (12 – 17 years) in 2017, 14% had tried e-cigarettes and half of these had never smoked a tobacco cigarette before trying e-cigarettes. 13

E-cigarettes have become more popular in Australia and overseas over the past few years. However, e-cigarettes and e-liquids are not safe.

- There are numerous reports of the batteries in e-cigarettes exploding causing burns and other injuries, including to the face, thigh and genital regions. 12

- Swallowing or spilling e-liquid that contains nicotine on the skin or eyes can result in nicotine poisoning. Internationally thousands of cases have been reported, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Young children are most at risk of poisoning from e-liquids. 12, 32-34 One Victorian toddler died as a result of poisoning from an e-cigarette in 2019. 35

- There is growing evidence that e-cigarette use can be harmful to health. E-cigarettes contain toxic chemicals that can damage body tissues. The health effects of long term e-cigarette use are unknown. 12

- Chemicals in e-liquids are not tested to confirm if they are safe to inhale. In the United States, there have been over 2,800 hospital cases of serious lung injury and at least 68 deaths linked to vaping. At least 400 patients were under 18 years old. Cases were strongly linked to e-liquid containing Vitamin E acetate, a food additive that is safe to eat but dangerous to inhale. Most patients had used THC containing e-cigarettes, but some had used nicotine containing e-cigarettes only. 36

- There is no conclusive evidence that e-cigarettes can help smokers to quit, and there is growing evidence that young people who use e-cigarettes may have an increased risk of taking up smoking. 12

For more information visit: https://www.quit.org.au/resources/policy-advocacy/policy/e-cigarettes/

Where can young people get help to quit smoking?

Quitline 13 QUIT (13 7848) - the Quitline is a confidential telephone information and advice service, which offers a tailored approach for young people. For the cost of a local call, Quitline counsellors provide encouragement and support to help people stop smoking.

Quit's websites have helpful tools and information on quitting:

- Quit Victoria www.quit.org.au

- Quit South Australia http://www.giveupsmokesforgood.org.au/

The nicotine patch, lozenge, mouth spray, gum or inhalator can be used to stop smoking by people aged 12 years and over. People aged under 18 years should speak to their doctor before using these medications. 37 It is strongly recommended that people in this age group discuss quitting smoking with a trained health advisor to benefit from using nicotine-based medications . 38

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2018. Canberra: AIHW; 2018. Report No.: Australia's health series no. 16. Cat. no. AUS 221. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2018/contents/table-of-contents .

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian burden of disease study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia, 2015. Risk factor estimates for Australia: Supplementary tables. 2019, Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/impact-risk-factors-burden-disease/data .

- Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, Egger S, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Medicine 2015;13:38.

- Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 2013;368(4):341-50.

- Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 2013;381(9861):133-41.

- Tait RJ, Whetton S, Allsop S. Identifying the social costs of tobacco use to Australia in 2015/16. Perth, WA: National Drug Research Institute, Curtain University; May 2019. Available from: http://ndri.curtin.edu.au/NDRI/media/documents/publications/T273.pdf .

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Canberra: AIHW; 2019. Report No.: Drug statistics series no. 32. Cat. no. PHE 270. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey-2019/contents/table-of-contents .

- Winstanley M, Wood L, Letcher T, Purcell K, Scollo M, Greenhalgh EM. Chapter 5. Influences on the uptake and prevention of smoking. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. 5th ed. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2014. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-5-uptake .

- Nathan A, Bain E, Hayes L. Smoking cessation trends in Victoria among demographic groups (2015 to 2018). Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2019.

- United States. Dept. of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease : a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010.

- United States. Dept. of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. In: Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24952/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes .

- Guerin N, White V. ASSAD 2017 Statistics & Trends: Australian secondary school students' use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances. Second edition. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020. Available from: https://beta.health.gov.au/resources/publications/secondary-school-students-use-of-tobacco-alcohol-and-other-drugs-in-2017 .

- White V, Williams T, Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, The Cancer Council Victoria. Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco in 2014 Canberra: Tobacco Control Taskforce, Australian Government Department of Health; October 2015. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/secondary-school-students-use-of-tobacco-alcohol-and-other-drugs-in-2014 .

- Campbell M, Ford C, Winstaney Margaret H. Chapter 4. The health effects of secondhand smoke. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Melbourne: The Cancer Council Victoria; 2017. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-4-secondhand .

- Dunlop S, Freeman B, Perez D. Exposure to Internet-Based Tobacco Advertising and Branding: Results From Population Surveys of Australian Youth 2010-2013. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2016;18(6):e104.

- Zoli M, Picciotto MR. Nicotinic regulation of energy homeostasis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2012;14(11):1270-90.

- Winstanley M, Greenhalgh EM, Bellew B, Ford C, Briffa T, Hurley S, et al. Chapter 3. The health effects of active smoking. In: Scollo MM, Winstanley MH, eds. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2015. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-3-health-effects .

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012.

- United States. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004.

- United States. Dept. of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking - 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Winstanley MH, Hall WD, Gartner CE, Christensen D, Vittiglia A. Chapter 6. Addiction. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. 5th ed. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2018. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-6-addiction .

- Parrott AC, Murphy RS. Explaining the stress-inducing effects of nicotine to cigarette smokers. Human psychopharmacology 2012;27(2):150-5.

- West R, Shiffman S. Fast Facts - Smoking cessation. Oxford: Health Press Limited; 2004.

- United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Office on Smoking and Health. Youth and Tobacco: Preventing Tobacco Use among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA.: United States. Public Health Service. Office on Smoking and Health 1994.

- Wellman RJ, DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Dussault GF. Short term patterns of early smoking acquisition. Tobacco Control 2004;13(3):251-257.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC CEO Statement: Electronic cigarettes (E-Cigarettes). Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government; 2017. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/ds13 .

- Greenhalgh EM, Scollo M. InDepth 18B: Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2016. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-18-harm-reduction/indepth-18b-e-cigarettes .

- Quit Victoria. E-cigarettes. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2018. Available from: https://www.quit.org.au/resources/policy-advocacy/policy/e-cigarettes/ . Accessed 23 October, 2018.

- Chivers E, Janka M, Franklin P, Mullins B, Larcombe A. Nicotine and other potentially harmful compounds in "nicotine-free" e-cigarette liquids in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 2019;210(3):127-128.

- Duxfield F. NSW Health Department finds not all e-juices are as nicotine free as they claim. ABC News. 12 Jun 2018. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-12/not-all-e-juices-are-as-nicotine-free-as-they-claim/9857540 .

- Govindarajan P, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, Chounthirath T, Smith GA. E-Cigarette and Liquid Nicotine Exposures Among Young Children. Pediatrics 2018;141(5).

- Vardavas CI, Girvalaki C, Filippidis FT, Oder M, Kastanje R, de Vries I, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of e-cigarette exposure incidents reported to 10 European Poison Centers: a retrospective data analysis. Tobacco Induced Diseases 2017;15:36.

- Wylie C, Heffernan A, Brown JA, Cairns R, Lynch AM, Robinson J. Exposures to e-cigarettes and their refills: calls to Australian Poisons Information Centres, 2009-2016. Medical Journal of Australia 2019;210(3):126.

- McArthur G. Nicotine kills baby. Tragedy after vaping liquid swallowed. Herald Sun 7 Feb 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Atlanta, Georgia (U.S.): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html . Accessed 5th March, 2020.

- Zwar N, Richmond R, Borland R, Litt J, Bell J, Caldwell B, et al. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2011.

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html .